Language models are increasingly used as agents: systems that operate over multiple turns, interact with tools or environments, and must recover gracefully from their own mistakes. In this post, we explore a setting where LM agents have seen some of their greatest success: software engineering, in which agents navigate codebases, write code, run tests, and even submit PRs.

A common way to train these agents is imitation learning: collect expert trajectories (from humans or a stronger LM via distillation) and fine-tune a student model on that expert data. While this approach underpins much of the recent progress in agentic LLMs, it suffers from a fundamental limitation that we examine here: covariate shift.

In our recent work, Imitation Learning for Multi-Turn LM Agents via On-Policy Expert Corrections, we expose the problem of covariate shift in SWE LM agents and propose a simple, practical fix that significantly improves training efficiency and agent robustness.

The Core Problem: Covariate Shift in Multi-Turn Agents

Imitation learning implicitly assumes that the model will encounter the same kinds of states at training time as it will at deployment. In single-step tasks, this assumption is often reasonable and even if there’s some distribution shift, current models can often generalize well. However, in multi-turn agent settings, distribution shift can worsen and compound throughout a trajectory.

When an agent makes a small mistake early in a trajectory—mislocalizing a bug, calling the wrong tool, or reasoning incorrectly—the rest of the interaction unfolds in a state that the expert never visited. Over many turns, these errors compound. Even if the agent doesn’t make any outright mistakes and just takes a different approach to solving the problem, the resulting trajectory can unfold in a completely different way than if the expert were in control. This phenomenon is known as covariate shift, and it is especially severe for LLM agents because the entire conversation history becomes part of the model’s input space for the following turn.

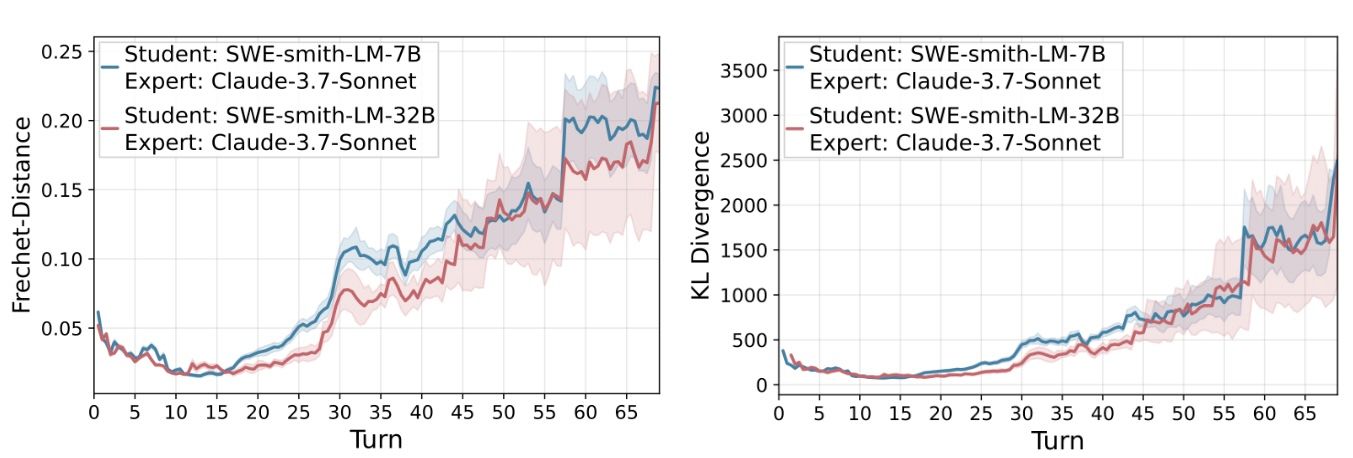

Figure 1: Even if a student model is trained to imitate an expert, divergence (Frechet distance left and KL right) between its trajectories and the expert’s grows throughout a trajectory.

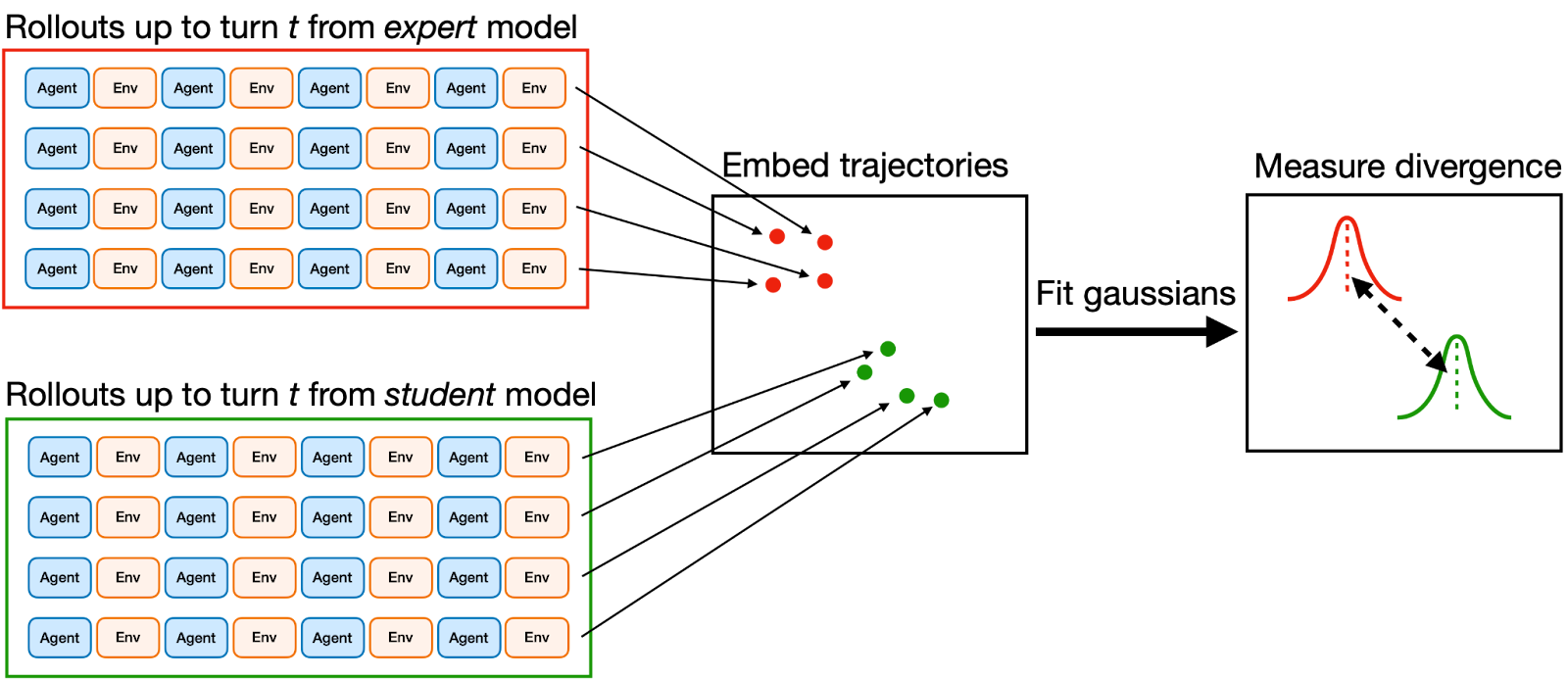

The divergence grows steadily over time, even for students explicitly trained to imitate the expert via behavioral cloning. Interestingly, the divergence from the expert seems to be very similar between a 7B and 32B model. In our SWE-agent experiments, we explicitly measure this drift by concatenating trajectory histories up until the current turn and getting a vector space embedding of the partial trajectory using an off-the-shelf text embedder (Qwen3-Embedding-8B). We did this over a set of trajectories generated using a small, non-zero temperature to get samples of the distribution of trajectories and then fitted a gaussian to the embeddings at each turn. We used these gaussians to estimate the divergence between student-generated and expert-generated rollouts to produce the above plots, using either KL or a modification of Frechet-Inception distance. As a baseline, we also measured the divergence within an expert-only pool of trajectories (which remained comparatively close to zero) to make sure that the growth in divergence wasn’t just from trajectories naturally spreading out across turns.

Figure 2: We estimate divergence between distributions of trajectories by using an off-the-shelf text embedder, fitting gaussians to the vector space embeddings, and measuring divergence between those gaussians.

Why Existing Fixes Fall Short

Classic imitation learning has long recognized the issue of covariate shift. The canonical solution is DAgger (Dataset Aggregation), which repeatedly:

- Rolls out the current policy on-policy.

- Queries the expert for the correct action at each visited state.

- Trains on those corrections.

However, naively applying DAgger to LLM agents runs into some practical issues:

- No full trajectories: Traditional DAgger only queries the expert for a single corrective action, making it hard to use trajectory-level verifiable rewards like unit tests.

- Higher inference/training cost: Querying the expert at every step requires re-running the model with a fresh context each time, which forces recomputation of the attention key/value cache. Without some tricks, the same problem applies during training.

At the other extreme, purely on-policy training (e.g., RL or rejection-sampled rollouts from the student alone) doesn’t benefit from the guidance of expert data. Our experiments also find that training on purely on-policy data can lead to instability on long-horizon agent tasks by reinforcing bad habits of the model, even when restricted to trajectories deemed “successful” under the verified reward.

On-Policy Expert Corrections (OEC): The Best of BC and RL

Our solution is On-Policy Expert Corrections (OEC)—a lightweight adaptation of DAgger tailored to modern LLM agents.

The idea is simple:

- Start a trajectory by rolling out the student model on-policy.

- Part way through the trajectory, switch to the expert model.

- Let the expert finish the trajectory to completion.

Crucially, the expert inherits the student’s history, so it is completing a fully on-policy trajectory. After generation, we can also incorporate verifiable reward from our environment (in the SWE agent setting, we throw out trajectories that fail to resolve the bug). Then, we use the OEC trajectories in SFT on the student model by training on only the expert portion of the trajectories since we found training on the on-policy portions of the data degraded performance.

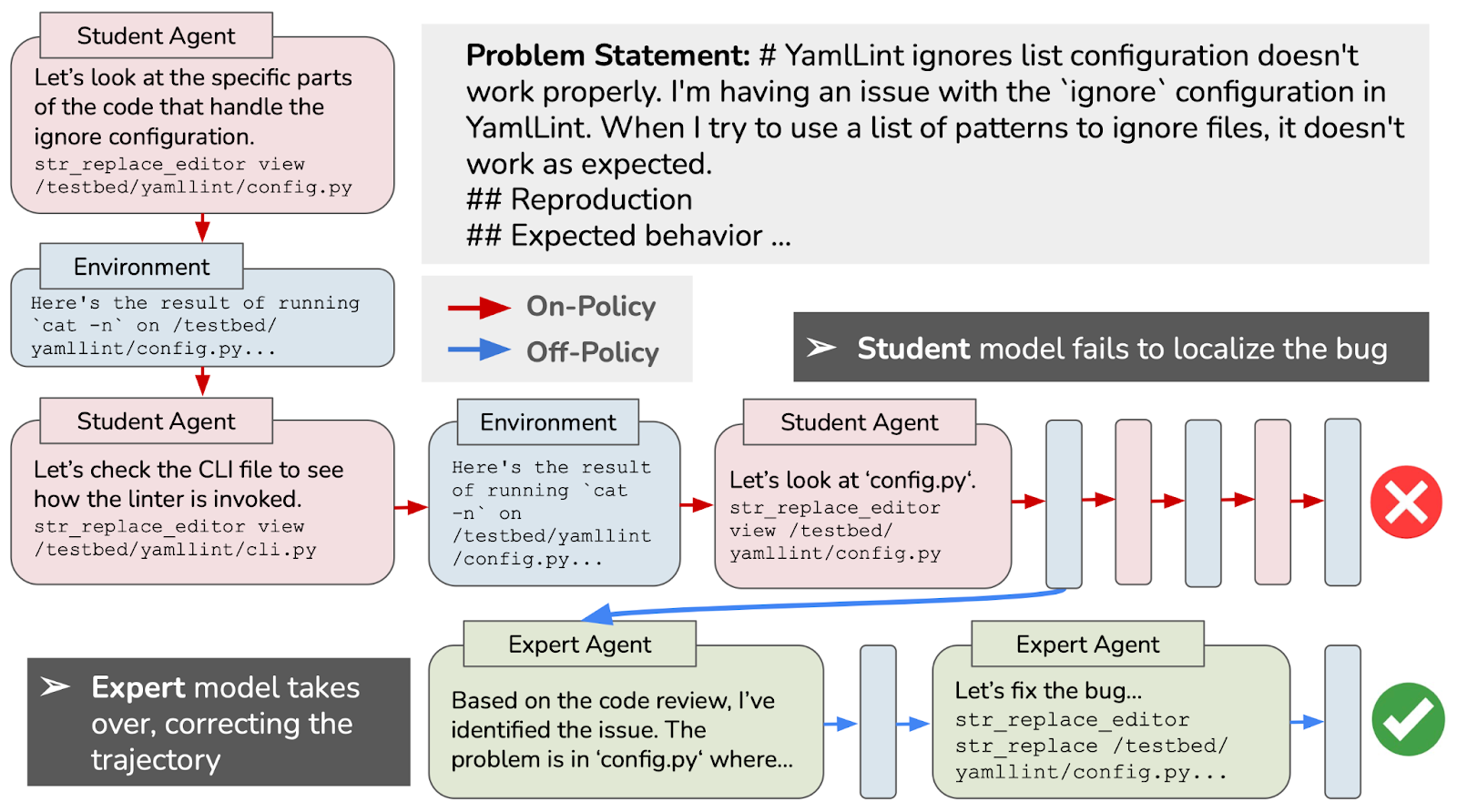

Figure 3: An example of a real on-policy expert correction in the SWE agent domain. The student begins the trajectory and fails to localize the bug, but after the expert takes over, it brings the trajectory back on track to finish localization then write and submit a patch.

OECs share the best properties of both imitation learning and reinforcement learning:

- The demonstrations are conditioned on on-policy states, providing in-distribution data.

- We get to learn from expert data and don’t have to rely on exploration to find good actions.

- We still obtain complete trajectories so we can make use of verifiable rewards (e.g., unit tests).

- We only have to recompute the full KV-cache a single time (when switching models).

Algorithmically, OECs are trivial to implement on top of existing agent scaffolds: sample a switch index (or switch when the student gets off track), rewrite the context to match the expert’s formatting, and continue the rollout with the expert.

Experiments: SWE Agents

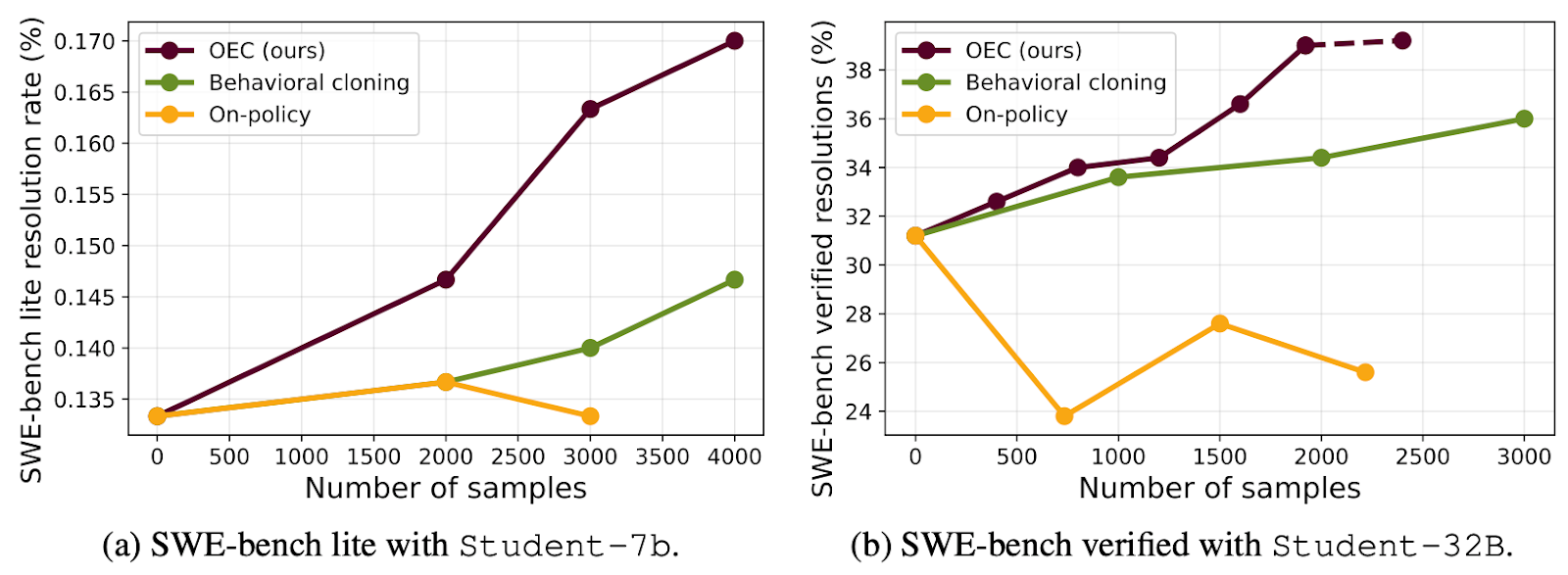

We evaluate OECs in the software engineering agent domain using the SWE-agent scaffold, and use SWE-smith as training instances and SWE-bench Verified for evaluation. These tasks require agents to explore a real codebase, identify bugs, write patches, and pass unit tests. We trained on data generated using (1) traditional behavior cloning, (2) purely on-policy rollouts, and (3) on-policy expert corrections across increasing data set sizes. Across all methods, we incorporated verifiable reward by discarding trajectories that failed to pass all of the unit tests in the problem instance.

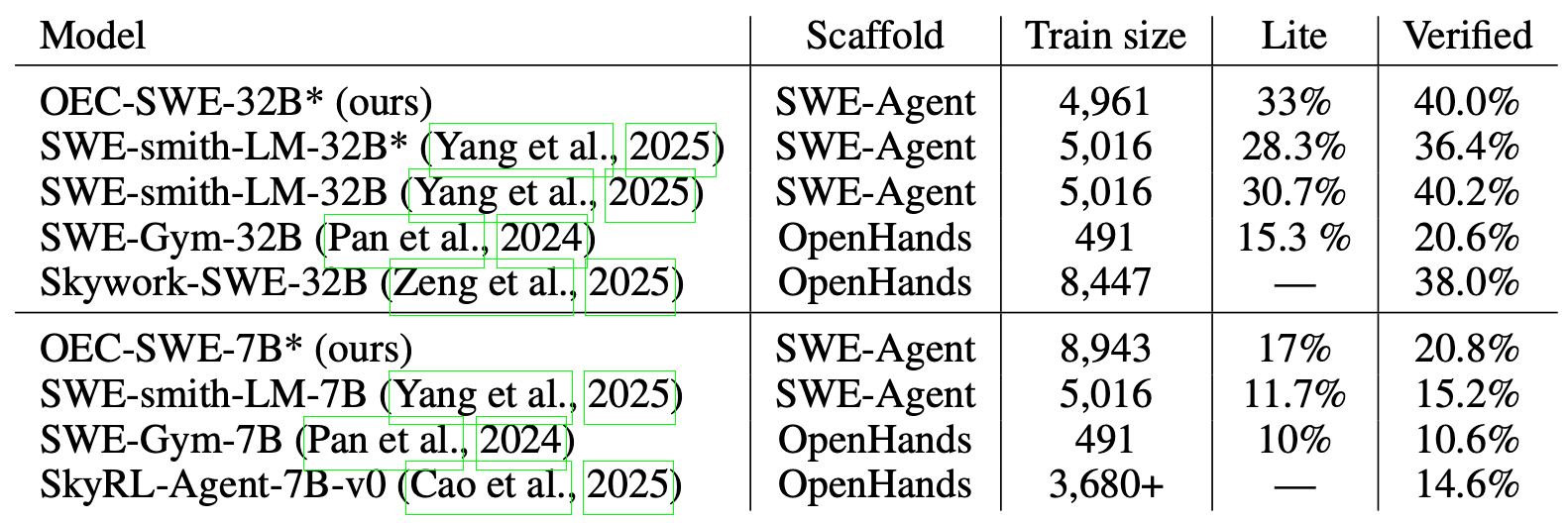

Figure 4: Resolution rates on SWE-bench for various models fine-tuned on top of the Qwen2.5-Coder family. Model names marked with * are based on our own evaluations; others are taken as reported in existing works.

Across both 7B and 32B models, we find:

- OEC trajectories consistently outperform pure behavioral cloning.

- Fully on-policy trajectories often hurt performance, even with rejection sampling.

- The best results come from mixing OEC and standard expert trajectories.

Figure 5: Resolution rates on SWE-bench while scaling dataset sizes between three trajectory collection techniques: (1) OECs (ours), (2) behavioral cloning (full expert trajectories), and (3) on-policy trajectories (full student trajectories).

For example, in the 32B setting, adding OEC trajectories improves SWE-bench Verified performance by several absolute percentage points over strong imitation-only baselines.

One surprising finding is that verifiable rewards alone are not enough to get gains from training with on-policy data. Even trajectories that pass all unit tests can be harmful if they contain degenerate behaviors (e.g., unnecessary file reads or repetitive behavior). In the above scaling curves, we only trained on positive trajectories that pass all unit tests, yet in the 32B setting, the purely on-policy trajectories degraded performance.

We found that simple programmatic filters, such as removing trajectories with repeated identical actions or long sequences of file reads, were essential for stable training across our experiments. This highlights an important lesson: agent data quality matters beyond verifiable rewards.

Related Work

A closely related piece of concurrent work came out of Thinking Machines recently where they introduce “On-Policy Distillation”. Their approach also tackles covariate shift by training on trajectories generated by the student policy itself, with expert supervision used as a process-reward signal on top.

There are some interesting differences worth highlighting:

- Training on expert actions: on-policy distillation works by using the expert's logprob of the student’s chosen action as a reward signal whereas OECs train directly on expert actions.

- Verifiable rewards: Our approach explicitly supports rejection sampling using environment feedback (e.g., unit tests), whereas on-policy distillation focuses on step-level supervision.

- No log-prob access required: OECs rely purely on supervised fine-tuning and do not require access to expert log-probs on arbitrary tokens (which most APIs don’t expose).

We see these methods as complementary, and we believe combining ideas from both lines of work is a promising direction for future research.

Takeaways

- Covariate shift is a real problem for long-horizon, multi-turn LLM agents.

- Pure imitation and pure on-policy training both have serious drawbacks.

- On-Policy Expert Corrections offer a simple, efficient compromise that works with modern agent scaffolds, closed-source experts, and verifiable rewards.

- Quality of training trajectories matters beyond simple verifiable rewards.

As LLM agents are deployed on longer-horizon and higher-stakes tasks, we expect these issues—and solutions like OEC—to become increasingly important.

View the paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.14895